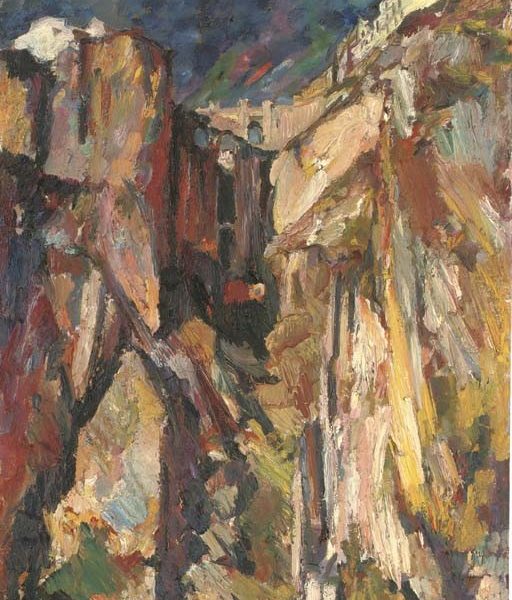

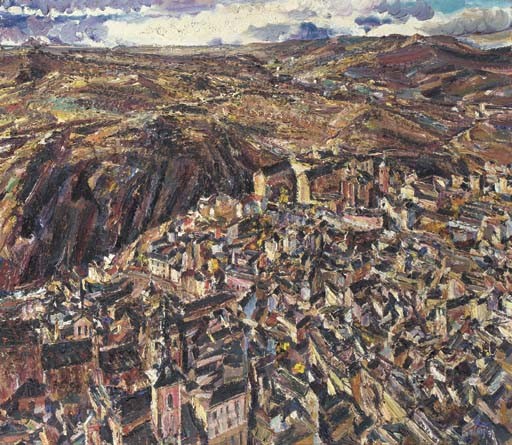

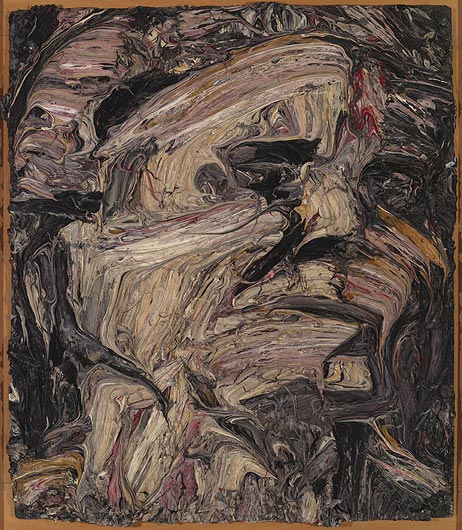

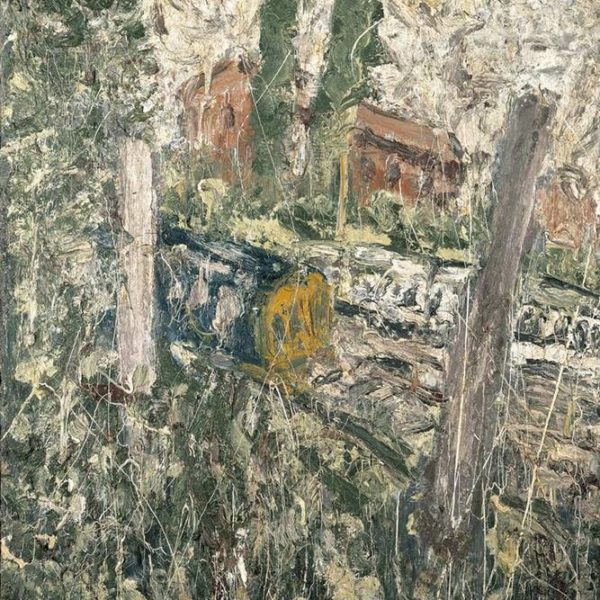

There is an upcoming exhibition at the Getty in Los Angeles, “London Calling”, that is opening July 26 and running through November 13, 2016. The show will bring together works by Bacon, Freud, Kossoff, Andrews, Auerbach and Kitaj. Although apparently different works than was included in the “Bare Life” exhibition that was in Munster, Germany, at the end of 2014 into the beginning of 2015 (no Bomberg or Coldstream, as far as I could tell), it does include many of the same painters and concerns.

After reading Catherine Lampert’s book, Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting, I located another book that featured her writing and that was the catalog from the “Bare Life” exhibition. It’s excellent. Not only in terms of the reproductions of the paintings gathered, but also in the caliber of the essays included. The opening essay is by Andrew Brighton, who was formerly Senior Curator at the Tate Modern. I’ve been mulling over his words for the past few months and wanted to bring some passages here to share.

He sets the stage:

“…since 1945; from the darkness of obtuse insularity, London emerged into the light of urbane cosmopolitanism. It is a story of British art and its public institutions joining an international culture of contemporary art. One way to complicate these accounts is to ask, what restrictions has this opening-up imposed? What cannot be done now that in the 1940s and 50s could be made, felt and thought with conviction? We should bear in mind that, for an artist born after 1950, the paintings of David Bomberg, Wiliam Coldstream, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff are the products of a situation that would be difficult, if not impossible, to recreate now.”

Andrew Brighton, “Explaining Pictures to a Living Heir”, from Bare Life, p.12

Brighton continues:

“David Bomberg went to the Slade School of Fine Art in 1911. Most art schools in Britain were established to improve the arts of manufacture. Fine art was a cuckoo that grew in the nest. It was accommodated as just one of the trade crafts taught. The Slade was different. It was founded forty years before Bomberg’s arrival as a school of fine art only, and as part of University College London. It enshrined institutionally Ruskin’s ideas of the moral and intellectual seriousness of art. Drawing was at the centre of the Slade’s pedagogy, and the teaching of drawing was dominated by Henry Tonks. For the imperious Tonks, being an artist was a vocation akin to a priest’s, and ‘a bad drawing was like living a lie.’ Modernism was lying. To depict the world truthfully was a glimpse of a higher spiritual order. In 1913 Bomberg was expelled for anti-social behavior after he punched a fellow-student. Until the mid-1920s he was one of the few serious modernist painters in London. Having abandoned modernism in his later years, Bomberg, the formative teacher of both Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, used to speak of “the spirit in the mass”. This would seem to accept Tonk’s metaphysic: the claim that in a long processes of looking and analogous mark-making, something of the metaphysical essence of the subject could be imparted to a painting. But this is an ideological gloss on a technical procedure. It is the procedure that persisted because of what it could enable. The problem it could solve was how to make paintings in a way that engages and records the artist’s attention. It facilitated painting as if it imparted something of the subject: the activity of depicting as a way to find an aesthetic necessity. It could inaugurate rules for the game to be acted out beyond the aesthetics of common sense. Painters inhabit the game; their activity discloses the transactions of a sensibility. Little is gained from imagining the subject ostensibly depicted in Bomberg, Kossoff or Auerbach’s work. Rather, they incite a search for an aesthetic rationality; the recognition of a sensate order made by another mind.”

Andrew Brighton, “Explaining Pictures to a Living Heir”, from Bare Life, p.14

This, it seems to me, is the crux of painting as a human depth activity and not simply depiction:

“…how to make paintings in a way that engages and records the artist’s attention. It facilitated painting as if it imparted something of the subject: the activity of depicting as a way to find an aesthetic necessity. It could inaugurate rules for the game to be acted out beyond the aesthetics of common sense. Painters inhabit the game; their activity discloses the transactions of a sensibility. …the recognition of a sensate order made by another mind.”

This is our problem.