I’d like to say something about the show that just closed at the Denver Art Museum a few weeks ago in October – “In Bloom” – that presented paintings of flowers by a variety of painters from the end of the eighteenth century through the beginning of the twentieth century. It was a surprising show. Perhaps what was most surprising was watching such a momentous shift occur in creative expectations and engagement during that period of time – a little over a hundred years, and watching that shift occur through the clarity of the apparently familiar motif of flowers. I mean, we all know flowers. Everyone likes flowers. Everyone loves flowers. So, this was a subject matter we all have some easy connection to – not like a dead rabbit or something.

In that sense the show was a crowd pleaser. And museums need to do that – I get that. But aside from presenting pretty pictures of pretty things, the show did something quite significant; it traced the occurrence and burgeoning of human subjectivity as a growing, overt influence and culturally acceptable ingredient in felt form during the course of the nineteenth century.

What I mean is, in the beginning of the exhibition, viewing the paintings done at the end of the eighteenth century, we see very expert, well wrought depictions of flowers. They are beautiful and they are sensible: responsibly providing a coherent production of a hopefully reliable world. To that extent these paintings are predictable and steady, and didn’t hold my attention for very long. Truthfully, I’m open to someone opening my eyes to something vital in them – I don’t mean to be dismissive. But in any case, when I visited the show, I quickly moved on.

What came next I did not expect. The Courbets and the Fantin-Latours knocked me out. Perhaps I should have been moved by the Delacroix, but I wasn’t. It was Courbet’s peonies. They were so felt. And it wasn’t just their erotic allusions – it was their erotic life-force in themselves as flowers. They are so full of mystery. They hit me. And then across the room from them was a whole wall full of Fantin-Latour. He always struck me as a very polite painter, lovely no doubt, but rather polite next to all those robust Impressionist painters. But in this context, presented as it was, I could feel his humanity. And curiously, he somehow felt the most contemporary of the entire exhibition. His china dated him, but he certainly didn’t look like an Impressionist or a Post-Impressionist, or a Modern painter. Nothing experimental, or flashy, or formally challenging. And yet there was an undeniably clear sense of him as a full-hearted, present person. We could feel him, his tenderness and care and attention: his singular personhood. Perhaps not unlike someone of our own twentieth-first century, unable to shake the residue of our individualized times, even as they set about to paint as straightforwardly as they could what was seen before them. His “Engagement Painting”. His Chrysanthemums!

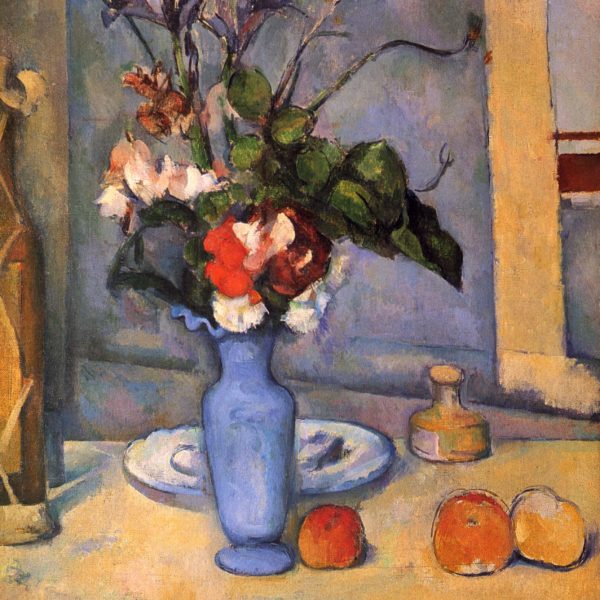

In the next room came the well-known Impressionist crowd – an unfinished Degas, an odd Monet that reminded me of a Dr. Seuss character (I’m trying to be descriptive here, not pejorative – but it was a pretty oddly shaped thing). There was a hallucinatory Renoir. And the Manets that couldn’t avoid the pathos of a man painting and knowing he is soon to die. Their brevity and fragility and beauty hit hard. But what took my breath away was around the corner – Cezanne’s The Blue Vase.

This painting shows, just to the left of center, a blue vase carrying flowers, some white and red ones (carnations?), some irises above them. To the left is an oddly placed bottle, split perfectly down the center by the edge of the canvas. To the right and a bit lower are some fruit that, at first glance, seem unfinished and roughly painted – above them what may be an ink jar, apparently floating above the table. Behind the blue vase a plate that is distorted and stretched beyond any reasonable repair. The table and walls blotchy with tonal indecision. There are many, many things to talk about in this painting – it is a wonder and a masterpiece. But the part that I would like to describe now is the way the edges of the vase are rendered. They are impossible!

What I mean is, as one’s eyes descend down, for example, the right side of the vase, the strong, sure line disappears and the edge of the vase blurs into the plate behind it. Then continuing to look down the side we pick up the line of the edge, again of the vase, coming up from the base — but those two lines, from above and from below, wouldn’t meet if we moved them toward each other through the blur. That is, there is no chosen edge; there are only two indecisive edges that don’t meet. We cannot physically hold such a vase – we can only attempt to see it. And I use the word “attempt” because the way Cezanne painted the vase is not as a fixed thing. It is a thing “becoming”, being found. That is, Cezanne is attempting to see the vase and attempting to paint this attempt. Indeed, what we are seeing in the painting is not so much a blue vase as a man’s perception of a blue vase. The overt subjectivity of this depiction is unavoidable. The flux of existence, and Cezanne’s courage to slow down and look hard and inhabit that instability and groundlessness, and from that place to bring back such beauty! It catches me in the throat. Andrew Forge, in his monograph on Monet, put it like this, “Academic art tells us that knowledge takes precedence over experience. Romantic art — which means all serious art since 1800 — says the exact opposite.”

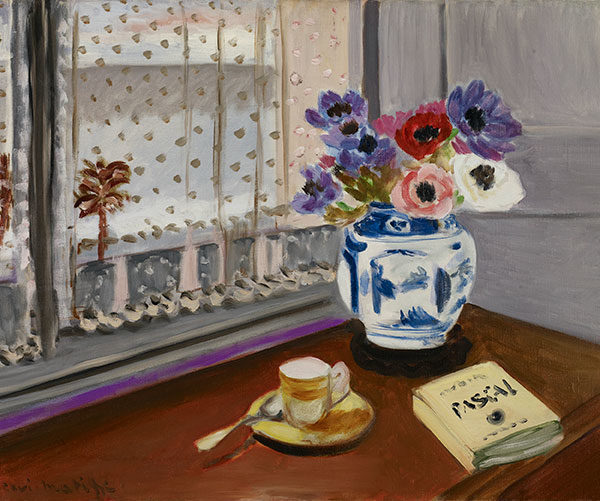

After Cezanne the flood gate was open and in flooded Redon and Van Gogh, Bonnard and Matisse! The magic of that seemingly simple Matisse, Still Life with Pascal’s Pensees, with its hidden and expansive light! (The digital image doesn’t begin to do it justice.)

Such an extraordinary leap from the beginning of the exhibition, a few rooms away at the end of the eighteenth century, and the end room, where the freshness of our newly found freedom invigorates and propels!

We were younger then. That was already a hundred years ago. So, where has our subjectivity led us and what does freedom look like now? I don’t mean the freedom to do what we want – that’s fairly plain to us all, and tired and worn. I mean the freedom to live and paint deeply, as if it matters – what does that look like now?